Why the RBA shouldn’t raise interest rates in February

While the idea of calling an end to rate rises will be an unpopular one among economists, the facts back my position.

Interest rate lag effect

In 2022 we saw eight consecutive months of interest rate rises delivering a total 3% bump to the cash rate. This was the fastest period of increases in over 20 years.

But history shows that it takes at least three to six months for rate increases to affect consumer spending behaviours and filter through to economic data.

I believe early rate rises are already taking effect. Yes, inflation has been driven by a combination of factors, such as higher energy prices on the back of the Ukraine conflict, and ongoing supply chain issues. But these are very much supply-side drivers.

As is many of the food shortages based on Australia wide flood events over the year in 2022 that is impacting the cost of many food staples and driving up prices based purely on demand. There’s little indication that demand for goods and services is responsible for cost increases, especially dietary staples such as potatoes and vegetables.

This is unfortunate because demand (not supply) is the side of the scale most influenced by interest rate rises. I believe that when supply chains fully reopen once more, this will prove far more effective at slowing inflation.

I also want to address the most recent inflation figure which might seem counter to my argument.

Just this month it was reported that the annualised inflation rate for November 2022 was 7.3%. This came after a promising October result of 6.9% which was a slight drop on the September figure.

This November uptick in inflation has caused all sorts of hand wringing among economists who say the RBA must now increase rates again at their first meeting in February.

What most of those economists aren’t saying is that November is a different beast to the month’s that preceded it. In November, consumers are gearing up for Christmas. Spending is exaggerated because of gifts, food, decorations, office parties… a whole host of seasonal expenses. This period also incorporates the Black Friday sales which deliver a frenzy of consumer spending.

Believing November is “typical” when making their interest rate call would be a huge mistake for the RBA.

Warning signs from the housing market

But it’s the property market that should be the canary in the coal mine for the RBA.

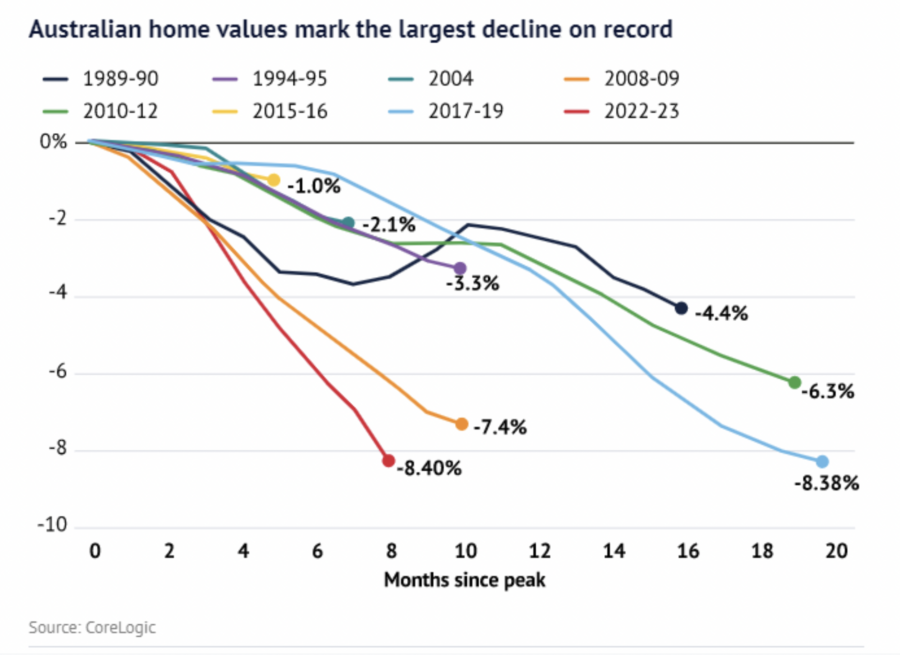

House prices have just experienced their fastest and most substantial fall on record as the graph below shows.

Some experts have predicted the total peak-to-trough fall in the current period will be 15% to 20% (that said, these same experts forecast a 40% price drop during the pandemic, so they are far from infallible).

The point is that falling house prices aren’t helping anyone except cash-rich buyers. Anybody applying for a loan, like the plethora of first homebuyers out there, will know their borrowing power has been slashed by the interest rate rises.

So, at a time when rental options are at crisis levels and there’s a severe undersupply of shelter, we are discouraging people from investing in new housing. The head of the HIA has already warned new home construction starts are dropping. Meanwhile construction costs will continue to rise this year.

There’s also a much wider economic reach when the building sector takes a downturn. The Australian construction industry is one of the nation’s biggest direct and indirect employment engines, so a hit to it means far fewer dollars flowing through the system. If this runaway train gets away from the RBA due to continued interest rate rises, they’ll have a hard time pegging back the losses.

The case for pausing

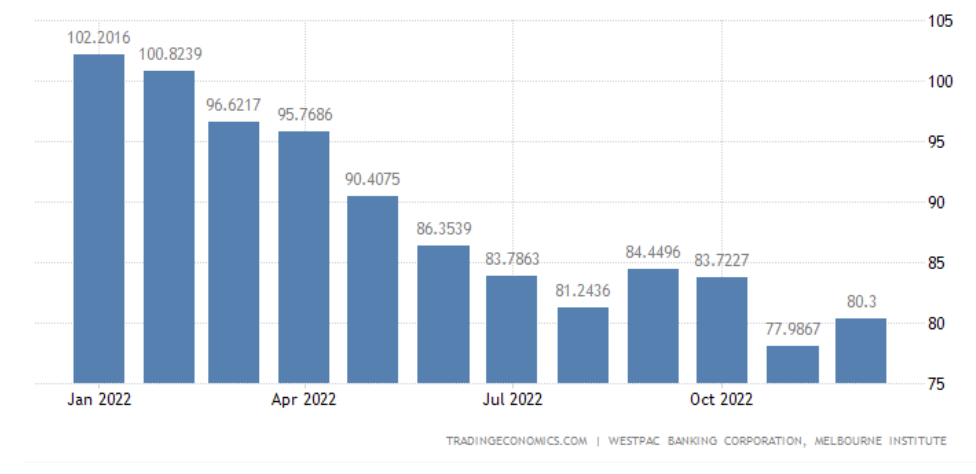

Well, consumer confidence is already running into the ground. The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment shows most Australians have a dire outlook about 2023 as compared to early 2022. When the graph below is less than 100 then it means that we have more pessimists than optimists. It is very clear that consumers here are heeding the interest rate rises.

Piling more rate rises on top of this risks further damage to consumer confidence. It will be much tougher recovering from these lows than many may realise.

When you take the “wealth effect” away from falling house prices and then add the pessimism of consumers, then spending has to reduce and this in line will see inflation drop as well.

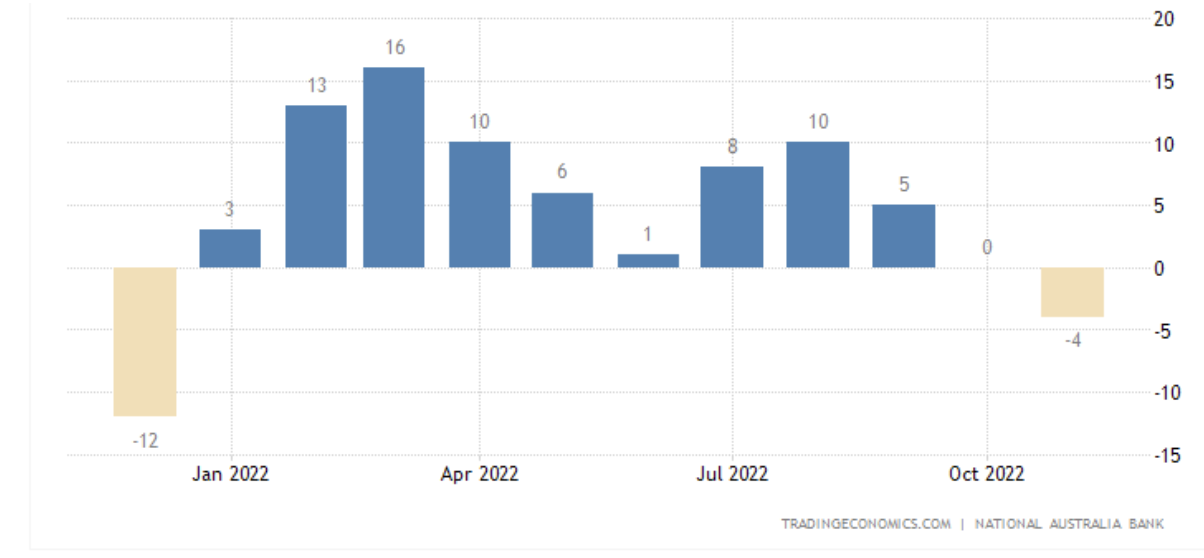

Business confidence is running lower too. The National Australia Bank Business Confidence Index has fallen below zero once more. Hit this with more rate hikes and we can expect businesses to plan for a tough future by cutting staff.

Finally, the fixed-rate interest cliff is looming. Many fixed rate loans will start to expire both this year and into 2024. This will see many borrowers come off record low rates of between 1% and 2% and be immediately thrust into a 5% loan product, more than doubling their interest repayments. That will be a huge shock to home finances.

Now is the time to take stock

Riding this sort of economic roller coast is stomach churning for the nation. Best they hold steady and read the landscape before proceeding.

Knowledge Hub Updates

- Don’t buy property in a trust before reading this - February 3, 2026

- When should you refinance? Navigating RBA rate cuts and loyalty rates - January 23, 2026

- What the latest inflation data means for borrowers with the upcoming February RBA decision - January 20, 2026