Are changes afoot in our lending markets

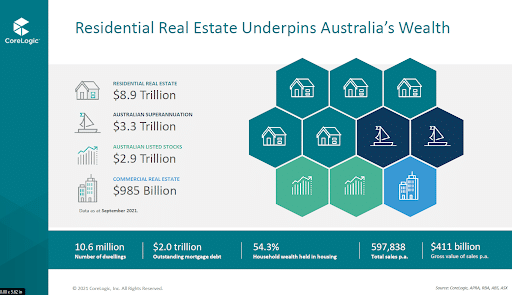

Australians are on a massive home shopping spree, borrowing to buy property at rates not seen before in this country. However, our bricks and mortar spendathon may be about to hit a snag as warning bells sound over soaring debt levels.

Home ownership bonanza

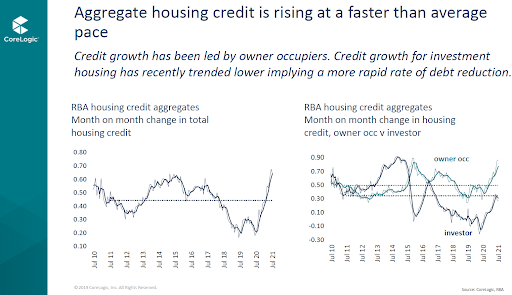

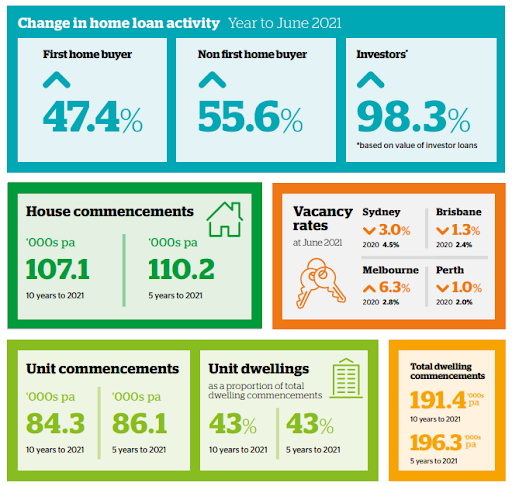

Recent ABS data has confirmed what most of us already knew – that the housing market is running hot, fuelled by low interest rates and ready access to credit, along with myriad government stimulus measures designed to get buyers into the market and spending up big. The confluence of these conditions has delivered a $38 billion spike in housing loans in the June quarter (of which $31.9 billion of this is owner occupier home loans and $6 billion is investor loans).

This growth in owner occupier loans is the strongest in five years and shows no signs of slowing.

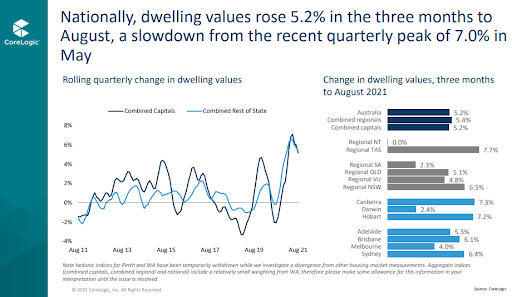

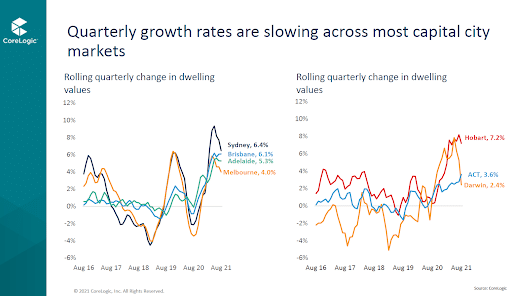

Experts have suggested that house price growth will finish the year at around 20 per cent, a phenomenal figure that has economists concerned.

More people than ever before are jumping on the home ownership bandwagon and, as the Treasurer pointed out earlier this week, “(in this housing cycle) a higher proportion of first home buyers and owner occupiers are entering the market”.

Getting more FHBs into their own home has been a major issue for successive state and federal governments for quite some time – how to help the next generation get a piece of the Australian dream of home ownership. So, it’s been a cause for celebration that the current batch of stimulus measures (including allowing people to use a portion of their superannuation for a house deposit and the government guaranteeing loans with less than 20 per cent deposit so customers can avoid the hefty cost of lenders mortgage insurance) has been a runaway success.

The downside is debt

However, all this borrowing translates to sharply rising household debt levels. People have access to very cheap credit at the moment and the banks, always keen for more customers, are lending, so people are seizing the opportunity to buy big-ticket items – such as a house.

But if household debt levels get too high, specifically debt-to-income ratios, a new challenge is created. It’s a bit like a giant game of whack-a-mole – solve one problem over here and then another pops up over there.

If the economy was ticking along in normal conditions, that is, without a pandemic and multiple lockdowns to stymie growth, we would see jobless numbers falling, and inflation and wages growing to keep pace with the spending bonanza. When businesses get lots of customers, they grow, by putting on more staff, adding more products and/or services and GDP increases.

However, these are not normal economic conditions. The Treasurer is trying to herd the cats of economic recovery by getting us to spend, (which we are – buying houses like they’re going out of fashion) but the other side of the scale to keep it all balanced – employment, wages and inflation – is not budging. Our jobless rate is creeping up and economists such as Saul Eslake think it’s actually much higher than is being reported.

Balancing the scales

So, what happens when household debt levels rise and our wages don’t keep up?

Well, warning bells sound because the economy is exposed to some stress points that represent significant risk. So significant that the IMF commented on it recently:

“Structural reforms to boost housing supply and targeted support for low-income households are needed to improve housing affordability. Macroprudential policy should be tightened and lending standards closely monitored,” a bluntly worded statement said.

House prices are rising, putting home ownership out of reach for younger people and those on lower incomes. And for those getting into the market, they need to borrow ever greater amounts to get their foot on the first rung of the property ladder.

Debt causes us to stop spending

On the one hand we’re seeing more people getting into home ownership, which is good because they’re creating wealth and long-term financial independence for themselves.

But high household debt can lead to a sharp reduction in consumer spending as borrowers try to funnel extra funds into the mortgage to reduce their debt levels. Or it can be that the minimum repayments are sucking up all their disposable income, having the immediate effect of cutting consumer spending. Either way, economic activity grinds to a halt.

And right now, the Treasurer is hoping a consumer spendathon is the ticket out of this pandemic-induced slump. A contraction in consumer spending couldn’t come at a worse time as he desperately fights to avoid two consecutive quarters of contraction – in other words, a recession.

Lending conditions

The additional risk sits with the banks as they hold a significant amount of loans where the debt-to-income ratio could be much higher than recommended levels.

Banks generally lend on debt-to-income ratio of around 6; that is, they will lend an amount six times the amount of the household annual income. So, for example, if a household has an income of $100,000, the bank will lend $600,000.

In the current climate (read: pandemic), banks have been encouraged to lend and there is a concern that there are loans on the books where the DTI is higher than 6, possibly up to 7 or 8. This is potentially not too concerning while rates are low, however, if we see a rate rise in the next few years (likely in early 2024, if RBA signals are to be believed) then this could push many customers into default.

To be clear, at this stage, risk of this seems low. The economic watchdogs are particularly sensitive to this situation following the 2007 global financial crisis that was triggered by a collapse of the US housing market under the weight of a mountain of “low-doc” loans.

It seems unlikely that we’re facing a similar situation here. APRA chair Wayne Byres told the House of Economics standing committee earlier this month that there was no sign of standards deteriorating and balance sheets were still strong.

But, the RBA and APRA are watching like hawks.

Meeting with the money men

So this troubling picture – house prices rising, debt levels soaring, wages growth stagnating – has led to the Treasurer calling on the money men, also known as the Council of Financial Regulators, to discuss “our macroprudential settings”. Simply put, they met to discuss our runaway housing market and what APRA and the RBA could possibly do to rein in the bolting horse.

The Treasurer revealed that he was talking about “carefully targeted and timely adjustments” for our monetary policy.

A change is surely coming.

So, what can be done?

Wee, there are a few levers that the Treasurer could pull to lower the current exposure.

- Rate rise: The RBA could lift the minimum rate that banks use for home loans. This would make credit more expensive and slow borrower activity. Governor Lowe has been very clear for more than 12 months – the RBA would not consider lifting rates until inflation and wages growth showed some signs of life and this has not happened yet. He has reiterated, almost monthly, that 2024 was the earliest the RBA would consider lifting rates.

- LVR restrictions: The loan-to-value ratio is a measure of how much money the bank lends against the value of the property. Anything above 80 per cent is considered a high LVR and is a riskier proposition (because the borrower has not established a good record of savings or demonstrated compellingly a capacity to repay). In the June quarter, more than 20 per cent of loans written were high-LVR loans. This is why banks insist on lenders mortgage insurance on high-LVR loans. These are usually the first loans to default. Regulators are now considering imposing limits on how many high-LVR loans banks have on their books as a way to limit risk to the balance sheet. This means it could become harder to borrow, particularly with smaller deposits. Banks will soon insist upon at least 20 per cent deposit. These measures were recently introduced in New Zealand by their Reserve Bank and this has had quite an immediate effect to reduce borrowings over the ditch.

- Greater scrutiny: The quality of lending is under the microscope, with APRA and the RBA training their laser-like attention on lending quality and household capacity to repay. This will have the effect of causing banks to pay closer attention to spending habits and savings habits and decision-making may become more conservative. For anyone considering a house purchase in the near future, you may find the banks seek greater levels of documentation to support your spending claims.

- DTI limits: The standard debt-to-income ratio is 6 (ie lending 6 times the income level, so, extrapolating on the earlier example, a household income of $200,000 a year would qualify to borrow $1.2 million). But as house prices continually rise and income remains static, implementing a hard and fast DTI limit could result in locking many out of the home ownership market. If DTI limits are introduced, this would have an immediate impact on house sales in the capital cities, particularly Sydney and Melbourne. House prices in these cities are already so high that only a very few high-income earners would be able to borrow on a DTI of 6 times. Anyone on an average wage (around $85,000 – $100,000) would be locked out.

With the current housing growth unsustainable based on lack of wage growth, this measure is, in a way, already being implemented but unfortunately it affects those on low wages more than our higher income earners, and therein lies the disparity that Government is concerned about.

Action is required

There is no doubt that action is required. Left unfettered, the housing market will continue its astronomical journey to the stars and Australia will quickly move from the second-highest mortgage debt levels in the world to the highest (we currently trail behind the Swiss).

The best lever that could be pulled to lower house prices and make home ownership accessible to more hasn’t even been discussed.

Supply. If Governments must make it easier for supply to be created, this will help address demand and be an effective tool to assist in managing house price growth.

But, the need is pressing and solving the supply issue is a long-term solution, so for now it’s likely that we’ll see a mix of all the tools being used.

My best guess is that we’ll see banks tighten their lending criteria, looking more closely at spending and disposable income. DTI and LVR levels will be under the microscope and loans will be smaller, more in line with capacity to repay, taking into account future rate rises.

For anyone considering a home loan, it’s important to weigh all your options and prepare for this new lending environment to give yourself the best chance of success.

The information provided in this article is general in nature and does not constitute personal financial advice. The information has been prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on any information you should consider the appropriateness of the information with regard to your objectives, financial situation and needs.

- Don’t buy property in a trust before reading this - February 3, 2026

- When should you refinance? Navigating RBA rate cuts and loyalty rates - January 23, 2026

- What the latest inflation data means for borrowers with the upcoming February RBA decision - January 20, 2026